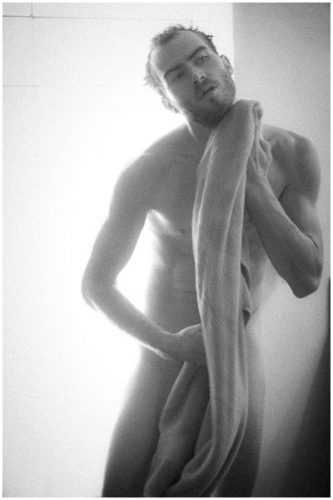

Up until 1902, photography had been concerned mostly with the ability to capture the reality of life, as a simple means of recording ordinary life as it naturally existed. Matthew Brady captured and documented the aftermath of Civil War battle sites and brought a reality to its viewers. Eadweard Muyrbridge managed to record that all four hooves of the horse could indeed leave the ground when it galloped. Historical travel places, horticulture, and etymology were being documented and cataloged. Through photography was a new wonder medium, it lacked artistic flexibility. Toward the end of the 1800’s there began a new movement in photography. It began among collectors of fine art, mostly of paintings, who wanted to move the realism of photography toward more of an art. They began to explore with the principals and theories of classic design and composition that had been developed by painters for centuries to begin to control and manipulate the photographic frame. They also refined new processes to give the images more of a painterly quality, often softer, becoming concerned more with the emotional impact their images would have on the viewer. Photography began to move in a whole new direction known as “pictorial” quality. It began with landscapes and eventually worked into portraits. Yesterday I mentioned a moment called The Photo-Secession, which was made up of a group of photographers brought to prominence by Alfred Stiegliz who owned a Saloon in New York and began to show images of this nature. Those photographers like himself, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Kasebier, Clarence H. White and of course Fred Holland Day (bottom right image) began to flourish and began to revolutionize the movement of photography into a more artistic format. Instead of the photograph dictating the parameters from which it could capture it put that control into the hands of the person taking the picture. Suddenly the photographer had artistic choices on how the image would eventually look. They could control the feel in texture and tone. Photography could finally evoke the expression of the photographer’s feelings and emotions to the viewer as painting had always done before.

Up until 1902, photography had been concerned mostly with the ability to capture the reality of life, as a simple means of recording ordinary life as it naturally existed. Matthew Brady captured and documented the aftermath of Civil War battle sites and brought a reality to its viewers. Eadweard Muyrbridge managed to record that all four hooves of the horse could indeed leave the ground when it galloped. Historical travel places, horticulture, and etymology were being documented and cataloged. Through photography was a new wonder medium, it lacked artistic flexibility. Toward the end of the 1800’s there began a new movement in photography. It began among collectors of fine art, mostly of paintings, who wanted to move the realism of photography toward more of an art. They began to explore with the principals and theories of classic design and composition that had been developed by painters for centuries to begin to control and manipulate the photographic frame. They also refined new processes to give the images more of a painterly quality, often softer, becoming concerned more with the emotional impact their images would have on the viewer. Photography began to move in a whole new direction known as “pictorial” quality. It began with landscapes and eventually worked into portraits. Yesterday I mentioned a moment called The Photo-Secession, which was made up of a group of photographers brought to prominence by Alfred Stiegliz who owned a Saloon in New York and began to show images of this nature. Those photographers like himself, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Kasebier, Clarence H. White and of course Fred Holland Day (bottom right image) began to flourish and began to revolutionize the movement of photography into a more artistic format. Instead of the photograph dictating the parameters from which it could capture it put that control into the hands of the person taking the picture. Suddenly the photographer had artistic choices on how the image would eventually look. They could control the feel in texture and tone. Photography could finally evoke the expression of the photographer’s feelings and emotions to the viewer as painting had always done before.

This is what makes me passionate about photography. Its ability to express ourselves as individuals. To share our unique perspective on the world. I find it ironic that in this modern area of instantaneous digital photography, where technology will allow you a plethora of ways to express yourself, that the pendulum has actually swung back to the old precepts of photography. To capture the realism, automatically, without any choice of artistic control other than pointing and pushing the button. Have we overall become lazy as a culture in our ability to explore the true creative nature of ourselves? There is a great majority of people that spend a great deal of time working on images. But most of the time that only means to wait for someone to move out of the shot, or to Photoshop out unwanted distractions. I see many of these images that still remain soulless, though they may be a beautiful well-exposed representations of the place.

>As a life long horseman, I've always taken the claim that it wasn't known whether all four of a horses feet could leave the ground at the same time with a grain of salt the size of Lot's wife: at the gallop, any rider of skill can feel it– not to detract from Muyrbridge's very impressive innovation.

But your point is still a very valid one: photography as means of expressing inward truths as well as outward reality certainly wasn't understood or accepted when the technology was new.